In the quiet hamlets of rural Jammu, from the forested slopes of Doda to the arid plains of Akhnoor, the floodwaters may have receded, but the damage to education lingers like a persistent shadow. Hundreds of schools stand as hollow shells—roofs caved in, walls cracked, and playgrounds turned to quagmires—yet the local education department’s indifference has left thousands of children adrift. In Kishtwar’s remote outposts, young Riya Thakur attends “classes” under a leaky tent, her textbooks salvaged from mud but her future uncertain. “The blackboard is a tree trunk; teachers come by boat sometimes. The officials say they’ll fix it, but it’s all talk,” Riya, a 12-year-old from a flood-hit family, confides, her eyes reflecting the frustration of a generation sidelined.

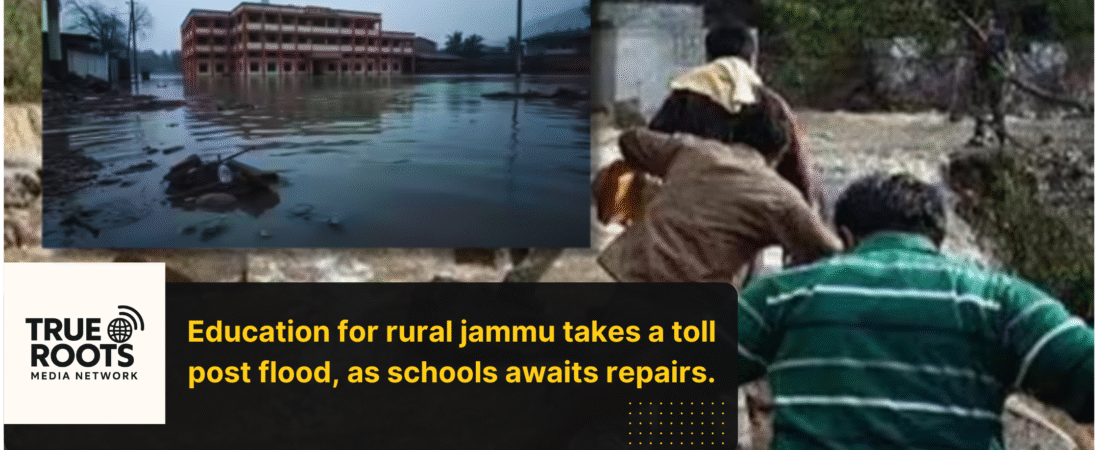

The August catastrophe wrecked over 500 schools across Jammu, displacing learning for 1.2 million students, with rural institutions hit hardest. Classrooms in Rajouri and Udhampur, submerged for days, now harbor mold and structural hazards, yet safety audits—mandated by the Directorate of School Education—are perfunctory or absent in remote areas. The floods, fueled by unprecedented cloudbursts, didn’t just destroy buildings; they eroded access, with unrepaired paths and bridges forcing dropouts. Parents in Reasi report a 10% enrollment dip, as families prioritize survival over schooling amid economic fallout.

The administration’s culpability is evident in its skewed priorities. Chief Minister Omar Abdullah’s ₹209 crore relief vow included school rebuilding, but bureaucratic snarls have disbursed only a fraction to rural zones. The department’s focus on urban reopenings, like those in Jammu city on September 10, leaves Doda’s 150 institutions in limbo, with audits delayed by “logistical issues.” Corruption taints the process—locals allege materials meant for repairs are siphoned off, a claim echoed in September 12 community meetings. Political unrest in Doda diverts focus, while the NEP 2020’s push for temporary centers remains on paper, ignoring rural realities like 60% literacy rates.

Children pay the price: traumatized by the deluge, they lack counseling, and girls face heightened dropout risks from unsafe commutes. Teachers, underpaid and overburdened, improvise with community spaces, but without supplies, it’s unsustainable. This systemic lapse isn’t oversight—it’s abandonment, widening urban-rural divides in a region where education is the escape from poverty. The department must expedite audits, allocate funds equitably, and deploy mobile units. Jammu’s rural youth deserve more than promises; they need rebuilt futures, not flooded memories.